Learning to Trust (Part 2)

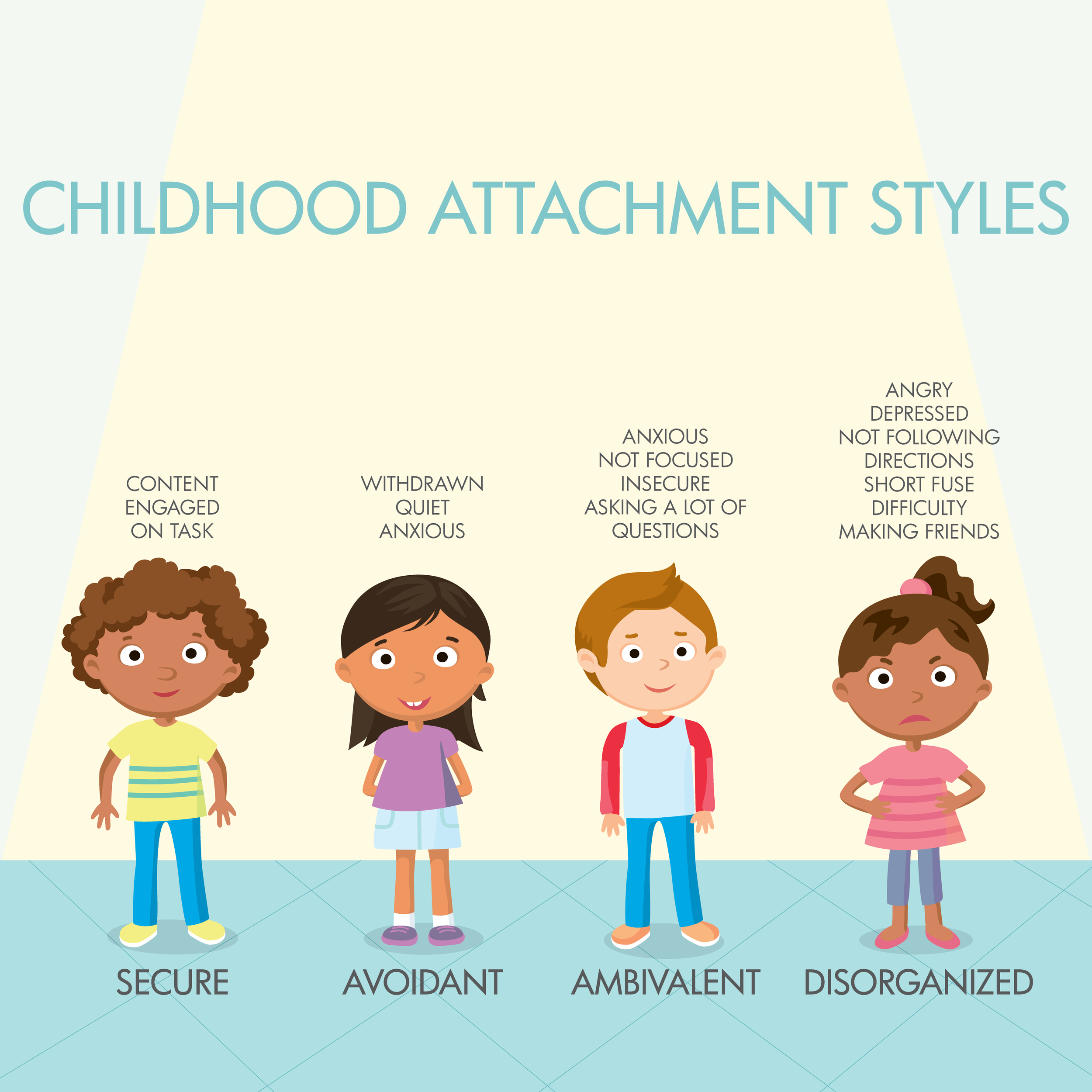

/In Part 1 of this mini-series, we identified four different attachment styles learned from our early experiences with caregivers:

Secure

Anxious/Ambivalent insecure

Avoidant insecure

Chaotic

These can be fairly unshakeable, until we begin to do the work of identifying our most prevalent patterns in relationships. We can then decide which to keep and which to let go of because they no longer serve us. COVID gave me the opportunity to do just that.

Identifying My Attachment Style

Looking back, I realized that my life had been pretty calm once COVID forced us to shelter at home. Sheltering at home meant I had to learn how to connect with my clients through Zoom. I gave up my office and, in return, I found time to throw in a wash and make dinner between sessions. For me, it wasn’t so painful or challenging as it was for so many others.

I really enjoyed not having to go out, make plans, or see people every day. I settled into a routine and felt gratitude for the time to just be. When life began to open up again, I actually began experiencing anxiety about having to see people and make small talk. I started on the path of assessing myself in my relationships.

Who was it easy to be with or not be with?

What made me disinclined to reach out to people?

What was keeping me from having the desire to get together with old friends or extended family members?

Besides being with my adult children, even making plans with family who I usually love to be with held no appeal. Was I depressed, or just going through a transition like everyone else? I wondered.

The answers that came to me were not new: I lacked motivation to reach out to those I’d had frequent contact with before COVID. This brought home the truth that I was operating from an avoidant place. In simple terms, I found it easier to be alone than to deal with the messiness of relationships.

Was I always avoidant? I wondered.

Early on, I generally waited until the other person invited me in and let me know that they wanted to make contact, get to know me or make plans together. It was as if I needed some sign that I would be accepted and welcomed. I considered myself temperamentally shy.

Then, I thought about how different my grandson is. He was a COVID baby surrounded by both parents and his “YaYa” and “Mema” through the first two years of his life. At three years of age, he is fearless in going up to new people he meets with a big smile. He introduces himself and asks, “What’s your name?”

There is an innocence and openness to belonging. Without expressing it in words, he assumes his needs will be taken care of. He is the poster boy for the secure attachment style.

That was definitely never me, at least not for as long as I can remember. By the time I was in 6th grade, I was going to a new school in a new neighborhood. I was fearful and unconvinced anyone would like me, even though no one would ever suspect it. I could never imagine asking my teacher a question that might tip her off that I wasn’t so smart as everyone said I was.

Learning Unspoken Lessons

When I think about it, I remember things that seem connected to the guarded stance with which I approached the world in my younger years. Being raised the oldest of six children, I remember clearly not wanting to bother my mother for anything. She already had so much to do to take care of us.

I was not asked how I was doing or how I felt. I just became her “helper,” literally begging to vacuum the living room when I was 5 or to take the baby out of his crib when I was 7. By the time I was 13, my sister and I were getting dinner ready, doing homework with my 3 younger brothers and getting them to bed.

I learned early on that I received attention for doing “adult” things well, and without complaint. That was my entry into decades of pleasing others to feel valued. In addition, I often sensed tension between my parents, without knowing exactly what was wrong. I observed banging doors and long silences, never knowing what started it or what would end it. Sometimes, there would be angry words at night that would wake me up; and in the morning, there would be no sign of conflict.

This unpredictability taught me to be vigilant for the next sign of trouble. Even if I had no power to affect its outcome, “knowing” gave me some sense of control. I learned how to “read” other’s moods and needs—which, ironically, has served me well in my profession. With my parents, I learned who needed to be distracted from whatever they were worried or angry about. Doing well in school became another strategy to please and placate, followed by learning piano and singing.

Another unspoken lesson I gleaned from our family's dynamics was that the only people to trust was family. While my parents seemed genuinely friendly with neighbors, relatives and some of their friends, it was clear that they didn’t share anything serious with them. Somehow, I learned that it was dangerous to let others in on the secret feelings you may be having: Don’t talk!

This really put me in a bind. If I couldn’t go to my parents because of the stressors they were experiencing, and I shouldn’t go to outsiders with anything troubling me, then who could I go to for guidance?

The answer, in my immature mind was, “deal with it yourself.” It made me very self-sufficient, to be sure. That was one of the blessings. However, it also led to years of feeling anxious when I was in over my head about something, and I could not ask for help. I would get flooded with the “fear of being found out” as a fraud and become paralyzed to taking action one way or the other.

Vulnerability, Conflict, and the Road to Growing Relationships

Learning how to acknowledge and deal with conflict is a skill that can actually make the relationship stronger. What my early life experiences did not teach me was that conflict and difficulties in relationships are normal. My younger self was terrified of disagreements, differences of opinions and ways of doing things. I feared judgment about being seen as “less than” or in the wrong.

All of this led, in my mind, to rejection and abandonment. So, I avoided any problems by denying them to myself and everyone else. I became the “go-along" girl, until going along became too dangerous to my physical and emotional well-being.

What saved me were a few good friends. One reminded me that staying in my unhealthy relationship was hurting not only myself, but my children, and my husband, for that matter. Speaking to someone on a regular basis gave me the safe space to explore who I had become in the relationship. This ultimately gave me the courage and strength to leave my marriage.

Years later, I found a Women’s 12 Step group, Relationships Anonymous. The group gave me the structure and support to be vulnerable, ask for help, and accept myself unconditionally. It also gave me the steps to take accountability for my failures, and to address conflict in a productive way. It allowed me to make the real changes that would enable me to change my world for the better.

When I reflect on my life, I realize I was lucky to do the kind of work that kept me in relationship with others. Hearing how my clients were dealing with their challenges gave me the courage to address issues in my life I may have otherwise avoided.

In my training as a family therapist, I learned to identify the roles and rules that are common in families, especially when there is unprocessed trauma. I learned that I was a “parent-ified” child, and that there are predictable issues that go along with that role, which I could relate to. That reduced the shame I felt for not being like my siblings.

I read about boundaries, about self-care, about conflict resolution. I joined a professional organization that provided opportunities for self-assessment in relationships around issues of power and privilege. Although the conversations were uncomfortable, they grew my capacity to be the humble learner instead of the helper.

All of these opportunities for self-awareness and growth led me to an even deeper exploration of my life experience. I could now explore that experience with curiosity, rather than a terror of being found to be lacking. These 9 steps helped me to change my attitude about myself and my behavior in my most intimate relationships:

I identified my typical way of relating in close relationships and read all I could on the different attachment styles. There are many online tools to help identify your attachment styles, which you can take here: Attachment Style Quiz.

I learned my partner’s attachment style.

I journaled regularly to stay in touch with my daily interactions and how I was handling them. I noticed consistent themes that came up. My most prevalent one was that I didn’t believe that my needs were important or would be met, even by people who said they loved me.

I identified my triggers—sometimes tiny situations—like when he’d forget to call about being late, or when he decided to watch a movie he knew I would hate without saying he just needed time for himself. Any time I felt my husband distance from me or disconnect, this kicked up intense, panicky feelings.

I connected present triggers to past wounds from childhood, especially those from when I was dismissed as being ridiculous for my feelings.

I could name what I needed: “I need to be able to talk to you about when I get triggered and feel too distant and alone.”

I practiced talking about where my needs were coming from using “I” language. I practiced talking about the themes and patterns that I developed as a result of earlier experiences. I practiced saying things like, “When you go watch TV without saying a word to me, I begin to feel alone and ignored as I did when I was a kid.”

I held my boundaries when my partner would forget and reminded him of my needs. Sometimes, if your partner doesn’t want to do the work with you, it may be time to reassess the relationship. For others, it may encourage your partner to also think about what they need, and to learn how to ask you to respond to their needs.

I shared conscious wound repairs: “I liked when you spent time in the kitchen with me while I cooked. It made me feel connected to you.” These can lead to even deeper conversations about our earlier experiences and how they have affected us in the present.

One of the most helpful outcomes of this 9-step process is my growing ability to relinquish the need to look for who is to blame when one of us is triggered. It also releases me of the need to create a story to go with assignment of blame of myself or my partner.

Instead of concluding that either I am not lovable enough for him or that he is not loving enough for me—which can lead to despair—I can step back, take a breath, and review these steps. My heart can remain more open and willing to be the compassionate partner I want to be. Understanding and working with our attachment styles can help us bypass the destructive strategies, so there is a greater possibility for a more authentic and compassionate connection.

What unspoken lessons did you learn from your experiences growing up?

Share your comments at the bottom of the page.

© Whatismyhealth

Special thanks to our resources:

https://www.mindbodygreen.com/articles/attachment-style-quiz

Understanding our attachment styles can help us bypass destructive strategies and find a more authentic connection.